This is a two-part series on gene editing in food plants. Part two will be shared tomorrow. The article originally appeared in AFBF's FBNews

By G.B. Crawford

Since the dawn of agriculture human societies have sought improvements in food plants. Over time this quest has involved such objectives as a sweeter fruit or better resistance to a pest.

Traditional plant breeding can achieve a desired result, but the process may take many years of trial and error to complete and nurture unwelcome traits. A series of scientific breakthroughs that began in the 1990s has created the opportunity to use a new approach. Researchers discovered that nucleases (enzymes) could remove specific sections of genetic material within a plant. They subsequently found that they could activate the expression of certain genes. As currently applied, the tool relies upon the plant’s natural biology to enhance a preferred trait without introducing material from another organism – much like traditional breeding.

Genetic engineering of a plant can require more than a decade to develop and exact a price tag of above $100 million. By contrast, researchers note, gene editing costs a fraction of that figure and may be completed much more quickly.

CRISPR

Within the past five years, a new editing technology known as CRISPR has given researchers a more precise way to target a particular gene. (CRISPR is an acronym for an appallingly long description of certain DNA sequences: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats). It is easier and cheaper to use than other editing techniques.

For farmers, editing promises increased harvest volumes on the same acreage at less cost. New plant varieties can reduce the use of water and fertilizer as well as losses due to pests and disease.

Consumers can benefit from larger crop yields with less production costs by boosting the abundance of nutritious foods and moderating their retail prices.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, agriculture must increase productivity by 50% within the next 30 years to supply adequate nutrition for the world’s human population. Most experts warn that current agricultural capability alone cannot meet this need.

Susan Jenkins, managing director of the Innovative Genetics Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, has concluded that gene editing offers a key to meeting the challenge. “We have the ability to modify plants to make them have better water use efficiency and also better nutrient use,” Jenkins said. “I am optimistic about how we use this technology, how it will be applied and the number of people it will benefit,” she added. “Because we can sequence the entire genome very inexpensively right now, we can make a change in a plant by using CRISPR. We can sequence the entire genome of that new organism and we can say exactly where other changes took place.”

The California facility has been a leader in developing improved cassava plants. Jenkins noted that researchers across the nation are working with other crops, including citrus and tomatoes.

Citrus Greening

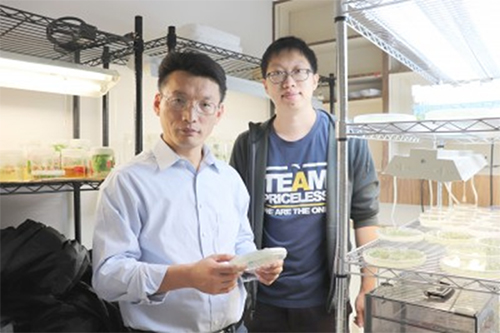

Citrus growers in Florida anxiously await the development of new varieties in their long battle with greening disease. Gene editing may develop a tree immune to the malady. Nian Wang, left, and his team at the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences are developing new citrus varieties with CRISPR.

Florida Farm Bureau photo: Microbiologist Nian Wang is employing CRISPR to develop such a tree at the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Citrus Research and Education Center in Lake Alfred. Wang, a pioneer in this research, has directed the project for nearly five years.

“We try to optimize gene editing for citrus,” he explained. “We want to identify which genes make the plant susceptible to the pathogen.”

Testing plants is a long-term process. “You want to make sure the genes you modify will not cause unwanted side effects,” Wang said. “You want to make sure you do the right thing by moving carefully.”

A commercially-viable plant will be forthcoming. But he cannot yet offer a timetable for its availability.

“We feel a real responsibility as scientists,” Wang said. “We want to find a solution as soon as possible.” Geneticist Tong Geon Lee is leading a gene editing project with tomatoes at the UF/IFAS Gulf Coast Research and Education Center in Balm. The goal is to develop a tomato plant that can be harvested by machine.

Lee noted that although this research has already produced new plants for greenhouse testing, he must complete a comprehensive assessment of new varieties before they can be released for general production. “Our first goal is to reduce plant height without damaging the fruit quality,” Lee said. “We don’t want to sacrifice fruit quality and other important traits for Florida growers.”

G.B. Crawford is director of public relations for the Florida Farm Bureau. Tomorrow, Crawford shares how private companies are looking into CRISPR and what consumers need to know about the technology.